This week is all about the images, smoking braids of hair, and all things 1700s printmaking.

THE HOTSHEET

This week we digitally restored more than 100 copper and woodblock engraved prints from books on piracy released between 1724-1860.

Work continues on our first two publishing releases, the first of which will be announced right here next week.

Digitization of newspapers continues, and we are working on creating a procedural system that will allow us to automate the ingest and quality control process.

MUSINGS

I was going through a lot of the books on the subject of crime and piracy from the 1720s and 1730s and started to wonder who was creating the artworks and how they were made.

So this week is all about show and tell.

After doing some research, I discovered that there were two techniques used at the time to create mass-printed artworks. Stone and later steel plate lithograph technology were still several decades away, but mass market art was everywhere in the form of broadsheets, pamphlets, and the works carried by booksellers.

The basics of the system of mass printing images is called Intaglio. This is the process of carving an image in reverse or negative into a flat, hard material that could then be covered in ink and stamped onto paper using a printing press. At the time, two different materials were widely used.

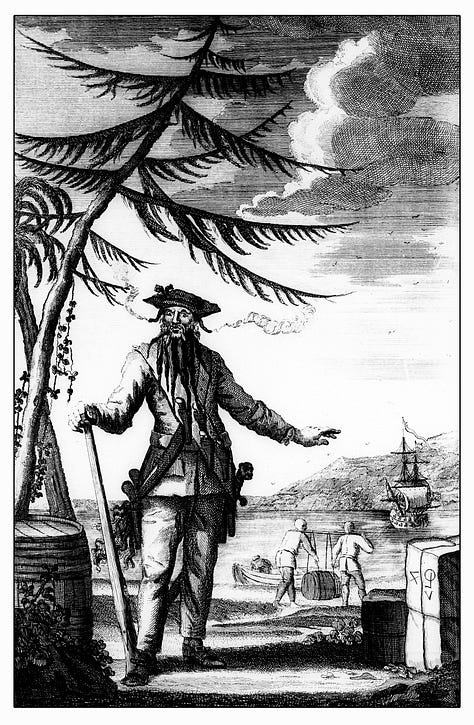

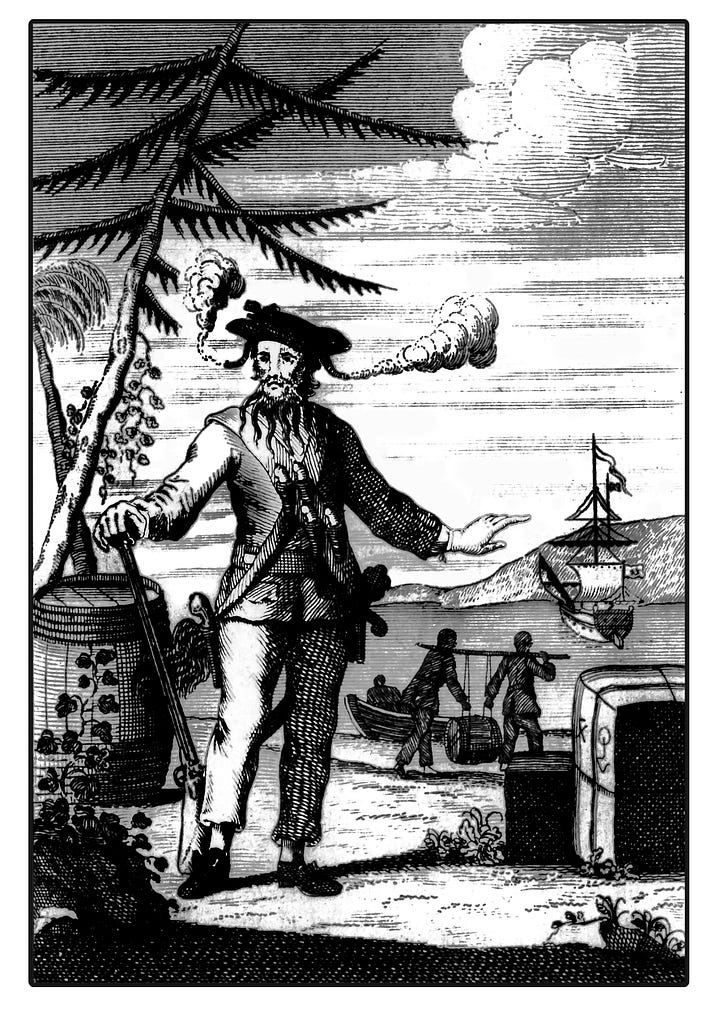

The first was copper. An artist’s sketch was traced onto a copper metal plate, and then a sculptor or engraver would etch out the image by removing material from the copper in reverse. This means that the material removed or subtracted creates areas where the plate would not touch the paper, and therefore leave no marking. This was a costly and time-consuming process, and the pages with the art had to be printed on paper using a machine different from what was used to print the text at the time. The plate or matrix, as it was referred to, could then be used to create large numbers of highly detailed images before the copper would wear out and require re-engraving.

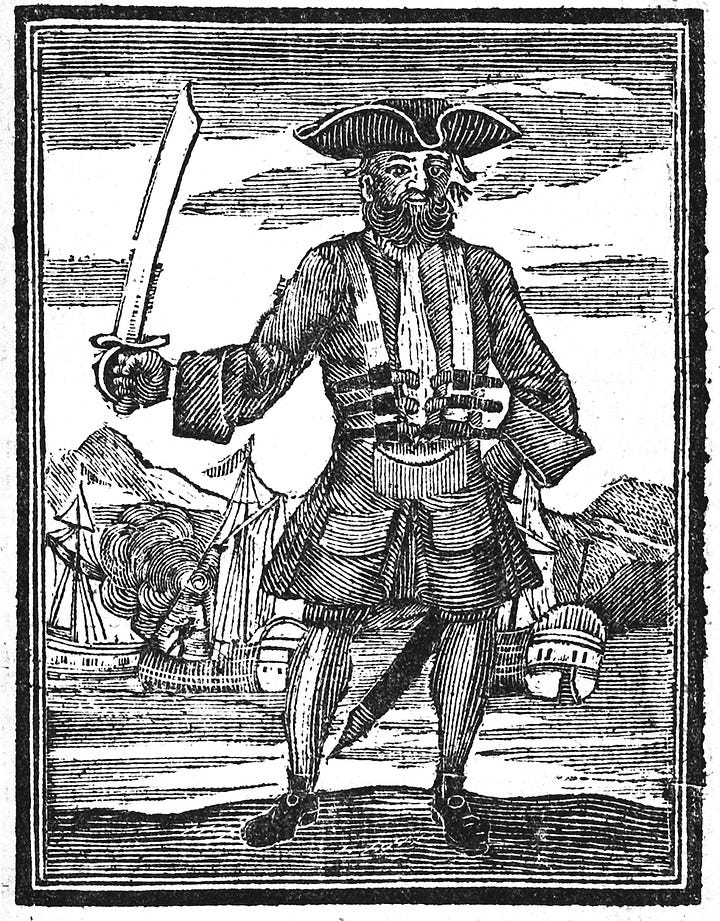

The second and more common material was wood. The engraving process was largely the same, except that lines needed to be thicker, and detail was harder to maintain beyond the first few hundred prints as the matrix quickly deformed and often chipped or cracked. These were cheaper to produce and quicker to make, and the woodblocks could be used on the same printing presses used to print books and other texts, so it is understandable why publishers more often favored them for economic reasons.

Here is a brief and informative video explaining the process.

For a much more detailed study of the process and its history and development here is a link to A History of Engraving and Etching Techniques a study published by the University of Amsterdam.

Moving beyond the technical aspects of the art…

The early 1700s marked the first time in England that literacy had become a staple of the middle class.

This happened for several reasons.

Up until the Glorious Revolution state run censorship of the press had severly limited what could be printed. The 1709 Copyright act set standard protections for authors and publishers for the first time, getting rid of the previous system and allowing a new legal path to hold people libel for defamation and misinformation. The final piece of the puzzle was the suspension of the Stationer’s Company a cabal founded in the 1400s that oversaw printmakers with an iron thumb and who severely restricted the industry for it’s own benefit. (source)

This led to an explosion of literary works, with author’s like Daniel Defoe building celebrity status and highly profiting off the success of their work.

This also led to…drumroll please…

PIRACY.

The book kind, not the- well you know.

Back to the point.

Everybody was stealing and slightly altering each other’s work. A word changed here, a slight adjustment to the title and boom.

Below are some examples of how this trend was also expressed in the printmaking.

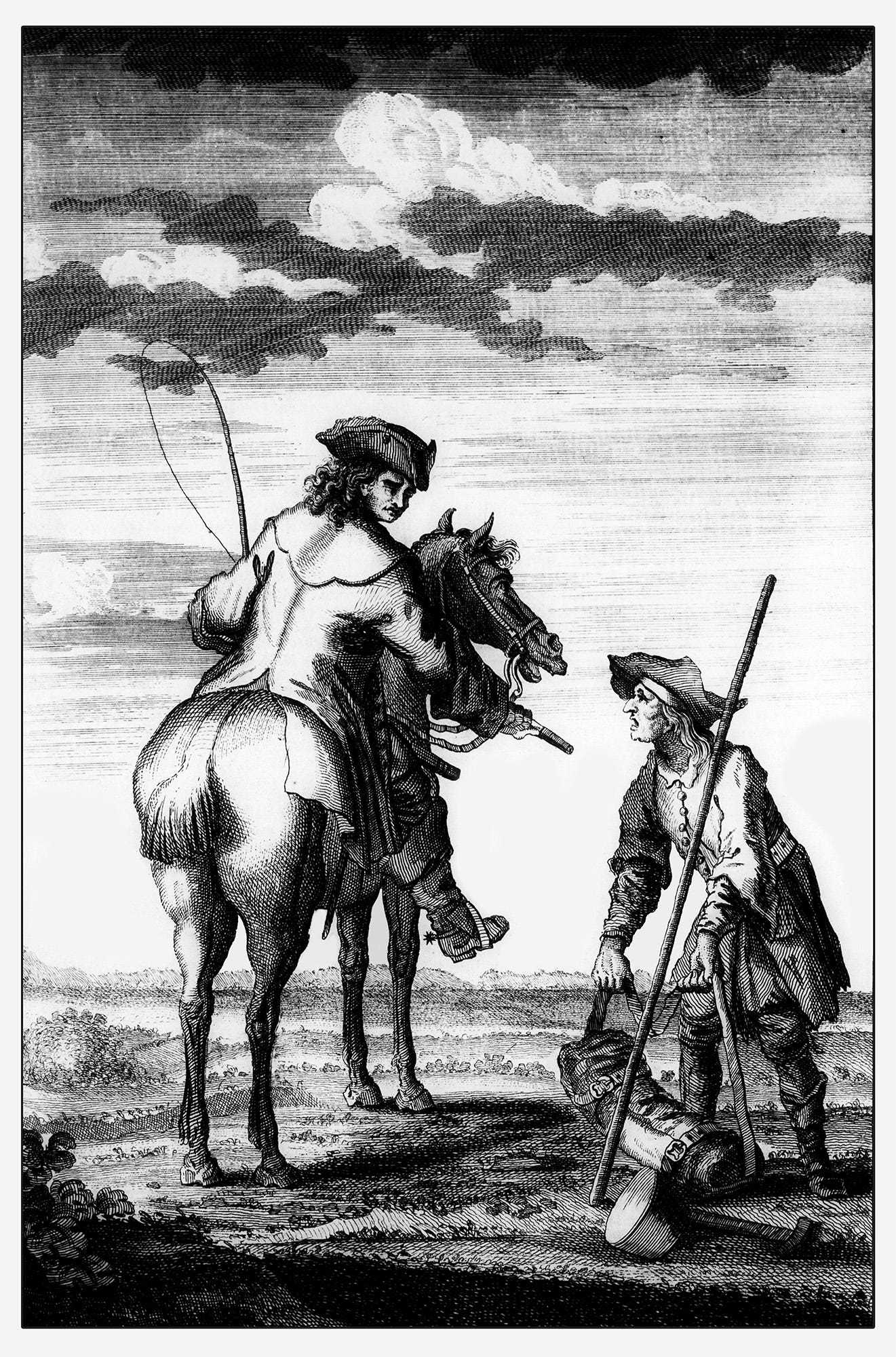

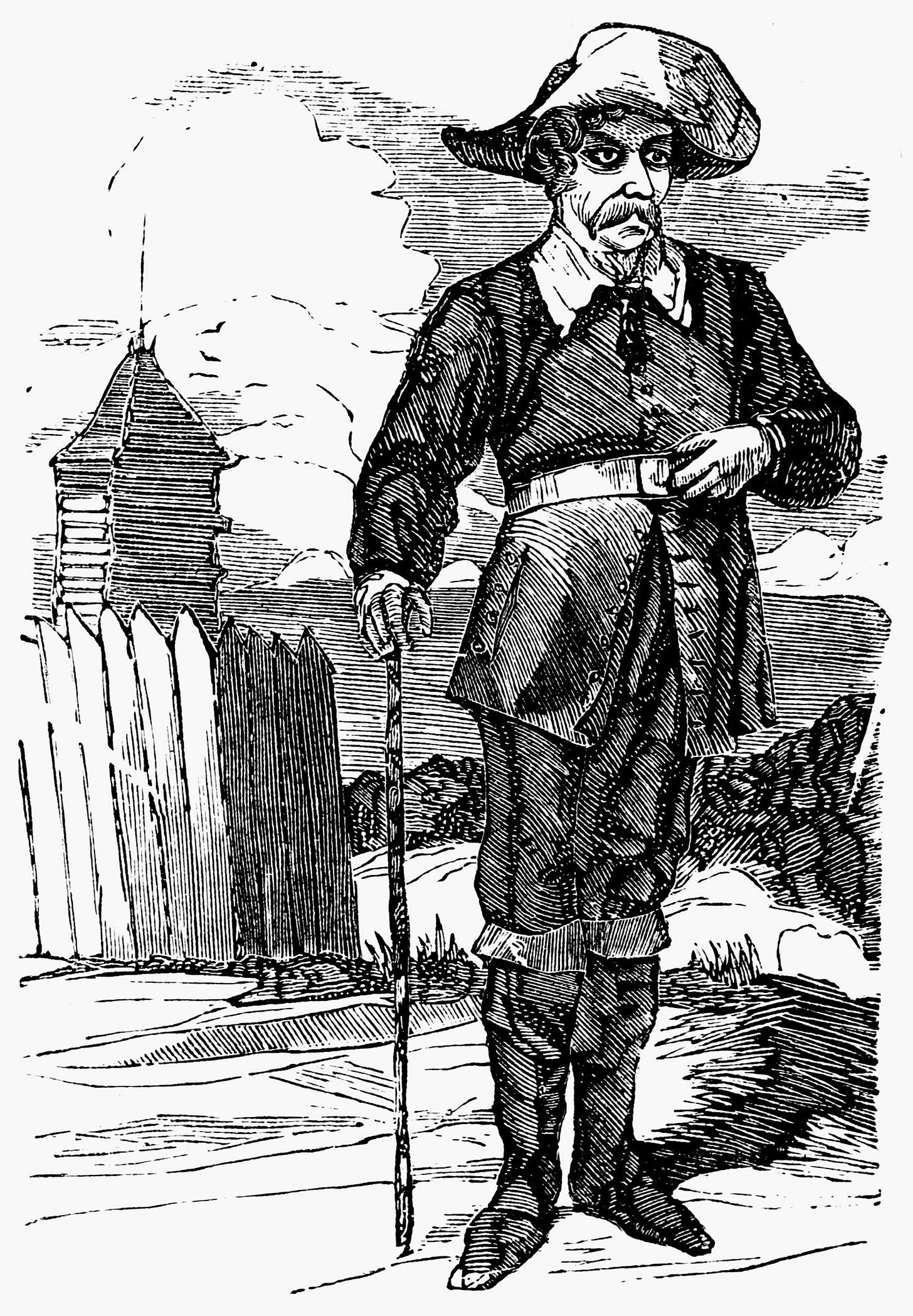

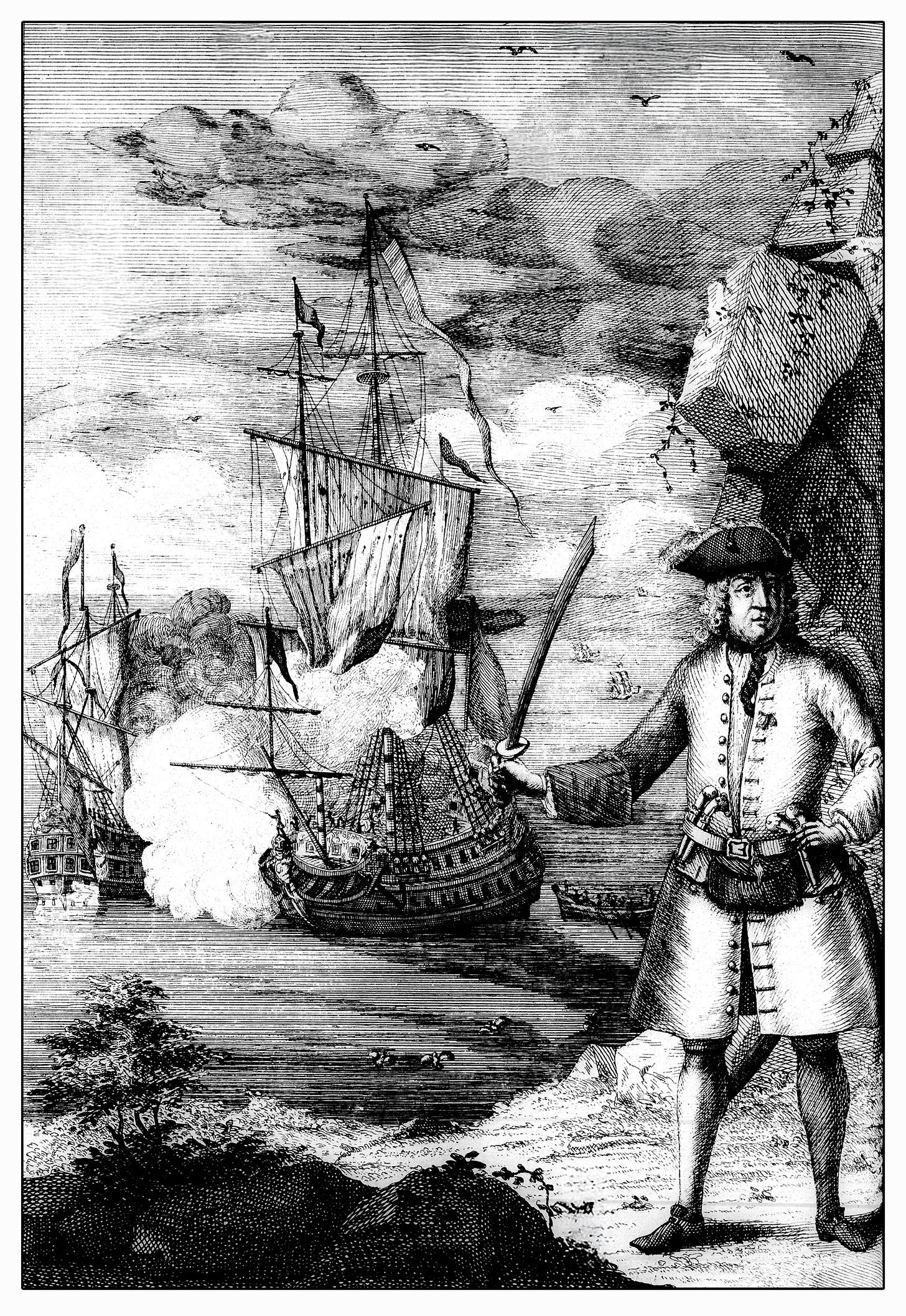

Let’s take a look at some of the depictions I’ve come across for Blackbeard. This is by no means an exhaustive analysis, but even with what I have found, it’s pretty clear how much borrowing was being done over the span of 80 years.

The first two are copperplate engravings from Benjamin Cole produced for A General History. The fur hat (1st edition) being replaced with a tricorn in the 2nd edition.

The third image was produced by James Basire for Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Lives and Adventures of the Most Notorious Highwaymen Murderers, Street Robbers &c. in 1734. The fourth image which clearly copied the 3rd was produced in 1758 for Captain Mackdonald’s, A General History of the Lives and Adventures of the most Famous Highwaymen, Murders, Pirates, Street Robbers and Thief-Takers, which was a blatent copy of the Johnson version.

(Interesting side note: copyrights only lasted 14 years at the time.)

The next two are woodblocks, the first of which is a clear copy of James Basire’s copperplate included in the 1725 release of The History and lives of all the most Notorious Pirates which appears to be an early knock off of A General History commissioned by Edward Midwinter. The even rougher woodblock, printed in 1769 is a knock off of the knock off printed in Glasgow. Interestingly the depiction of Blackbeard still seems to be derived from the Benjamin Cole copperplates.

The last image is from a book titled the Voyages of Edward Teach published in 1805 where the lineage of both the Benjamin Cole and James Basire images can be seen.

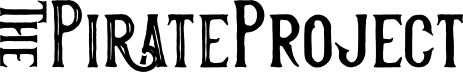

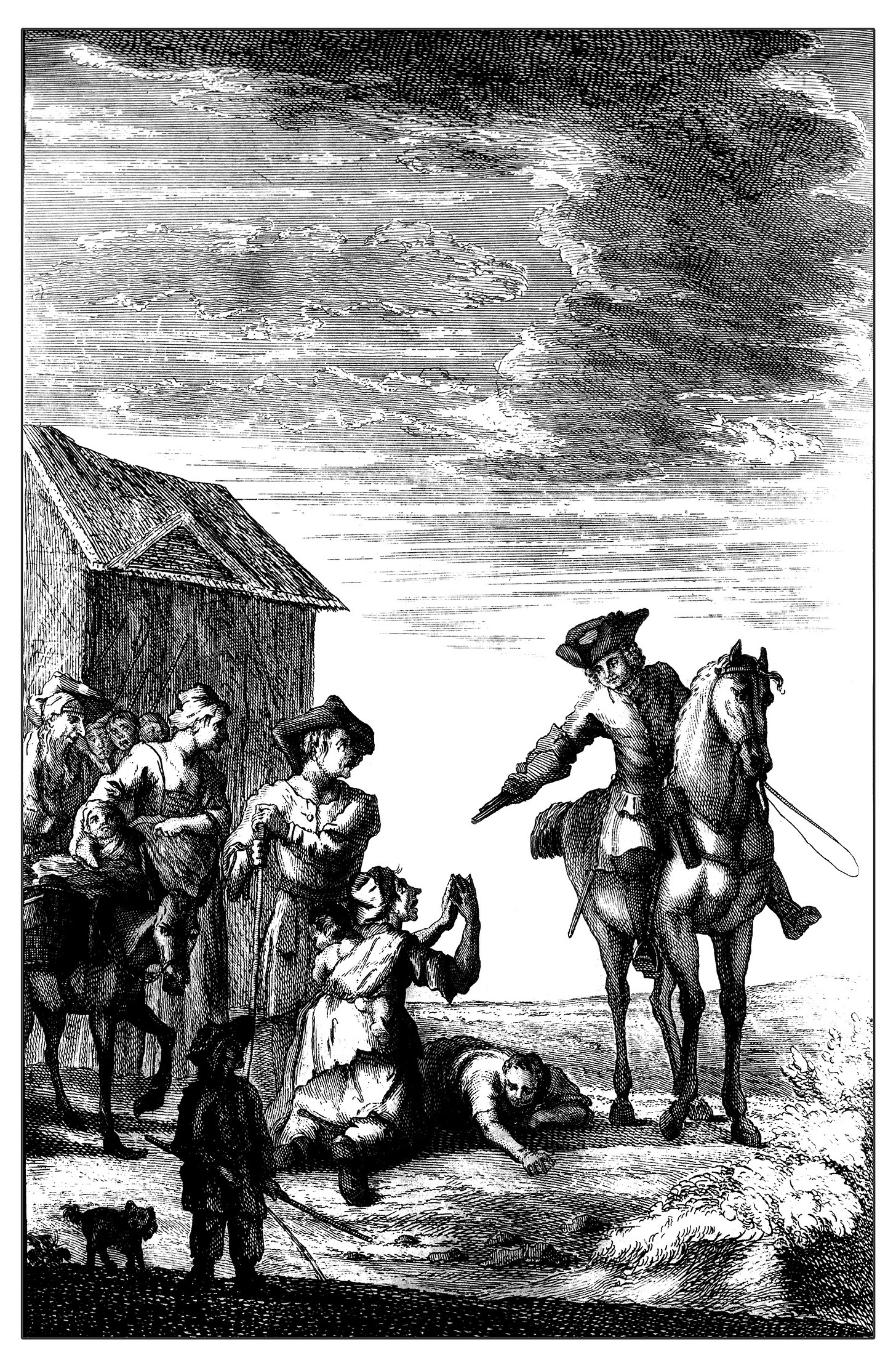

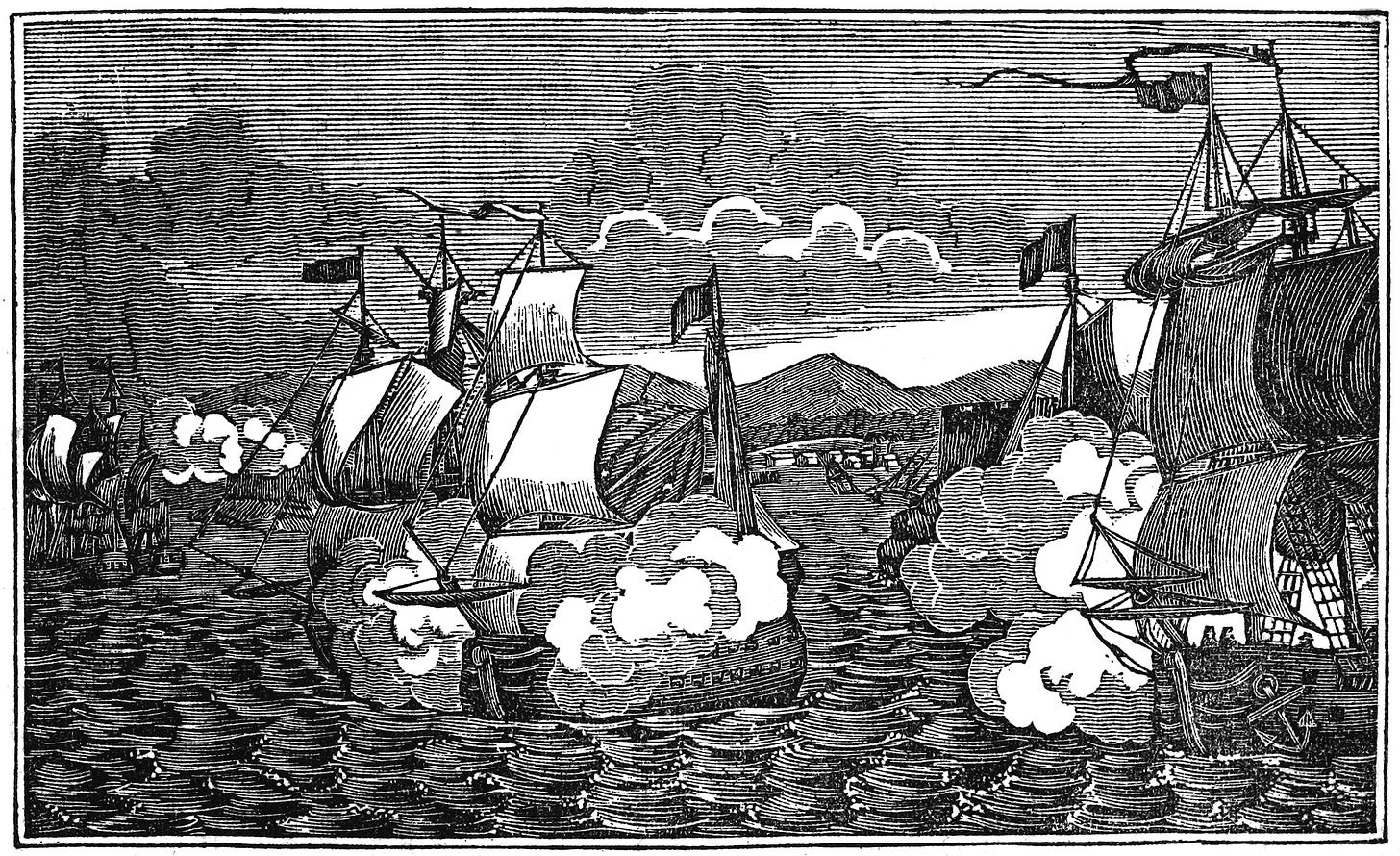

Lastly, I want to share some of these amazing works that have been digitally restored. It’s really hard to find high-resolution versions of a lot of this material so feel free to use these however you like.

Enjoy the art, and thanks for reading!

Help support the project!

Though we are only accepting pledges for future paid tiers in the substack please consider supporting us now at the link below

The Pirate Project is a multi-media experience that investigates the history of 18th Century Pirates using 21st Century forensic technologies launching later in 2025.

Jonathan Pezza is a multi-award-winning writer, filmmaker and podcaster living in Los Angeles, California. To listen to some of his other work in fiction, please visit linktr.ee/cmanthology

The Knightville Workshop produces and distributes cutting-edge immersive audio and transmedia content designed for tomorrow’s audiences.

©Knightsville Workshop 2025

I always like to say that 18th century print in London alone featured more piracy and theft then any actual pirate did. Its insane. Not to mention how many reprints or slightly reworded titles would appear even centuries later. There are chapbooks in the 1810s that are word for word taken from knock offs of A General History.